NEW DELHI, India: The government officials equipped with bulldozers arrived just before dawn, tore down the row of shanties as its baffled residents watched sadly nearby in the heart of New Delhi.

“We were so frightened,” said 56-year-old Jayanti Devi as she attempted to salvage what was left of her belongings, reported CNN. “They destroyed everything. We have nothing left.”

For the last 30 years, her home had been located next to an open sewage drain and on a dilapidated sidewalk directly across from the expansive Pragati Maidan complex, a well-known convention center in the Indian capital that will this week host the G20 leaders.

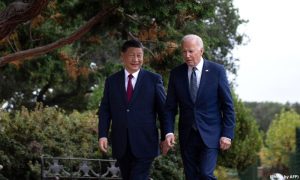

But when they arrive for the crucial summit, US President Joe Biden, French President Emmanuel Macron, and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak won’t see the house.

Devi is among tens of thousands of New Delhi’s most marginalized residents who have been evicted from their homes in the lead up to the G20 meeting, as authorities embark on a mass demolition drive in neighborhoods across the city, citing the “illegality” of these structures as their justification and claiming they intend to rehouse some affected communities.

Yet, activists have raised concerns about the timing, contending that these demolitions are part of a broader “beautification” campaign aimed at eradicating beggars and slums to impress foreign dignitaries.

The image that Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants to project at the G20 is one of a modern superpower, a leader of the Global South, and a voice for impoverished nations. However, critics argue that the government is concealing one of India’s most entrenched and enduring problems.

Harsh Mander, a social activist working with homeless families and street children, observes, What strikes me most is that India, the Indian state, is ashamed of ostensible poverty. It doesn’t want poverty to be visible to the people who come here.

In a written response in July, the Indian government denied any connections between the home demolitions and the G20 summit. CNN reached out to both the New Delhi and federal governments but received no response.

Delhi has long epitomized stark disparities, where millionaires reside in lavish mansions adjacent to homeless families living on the streets. Approximately 16 million people inhabit the capital, with only 23.7% residing in “planned” or “approved” neighbourhoods, according to a report by the Centre for Policy Research. The rest live in slums, villages, and unauthorized areas.

In April, Savita and her four daughters watched their settlement, an unauthorized neighbourhood near the 14th-century Tughlaqabad Fort, crumble before their eyes. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), is responsible for the demolitions, claimed encroachments on the land and illegal construction. Residents received notices to remove “illegal constructions at their own cost” within 15 days, according to court documents.

More than 100,000 residents in the Tughlaqabad area lost their homes in April, according to a Supreme Court petition. With nowhere to go and no funds to rent apartments, many, including Savita’s family, were forced to live under tarpaulin sheets on rugged land, enduring torrential rains and floods. During the day, they begged nearby policemen for bread, and at night, they lived in fear of danger lurking in the dark woods.

This isn’t the first time the Indian government has carried out slum or shanty demolitions ahead of a major international event. In 2010, beggars were forced off the streets of New Delhi, and slums were destroyed in preparation for the Commonwealth Games, disrupting the lives of tens of thousands.

Activists argue that it’s unfair for the government to target poor families for living on unauthorized land. Harsh Mander emphasizes that the government does not acknowledge that illegality has been imposed on these poor people. That’s because this city has been planned in a way where there is no place for them to live legally. The demolitions are being done with extreme cruelty.

While the Delhi government claims it intends to rehabilitate families like Savita’s, she says no help has arrived, and she is fighting her case in court. Her family now resides temporarily with a relative in a cramped shanty settlement, surrounded by squalor and the stench of cow dung.

Since assuming the presidency of the G20, India has positioned itself as a leader of emerging and developing nations, advocating for the Global South, particularly in addressing challenges such as climate change and food and energy security. However, activists highlight the irony in India’s image as its poorest citizens struggle at home.

People are dying on the streets in the cold winter, and we are demolishing homes, says Mander. There must be a fundamental right to life… to live with dignity.

For Savita, standing amidst the rubble of her former home, dreams of stability and a better life for her family have been shattered. “I wanted my children to grow up here. I wanted to give them a stable upbringing,” she laments. Now, her children study amidst garbage heaps, and her family’s future is uncertain.

As India seeks to project itself as a global leader, the plight of its marginalized citizens remains a stark reminder of the challenges it faces in realizing its vision for the future.